Richmond Industrial Fire

2 years ago

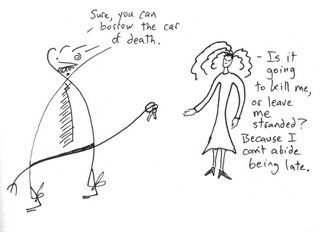

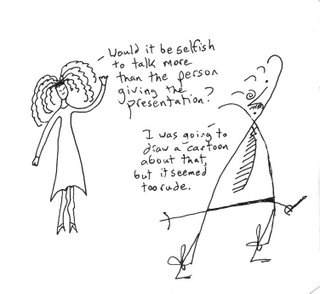

playing with my cartoons.

playing with my cartoons.I am too tiny in this world, and not tiny enough

just to lie before you like a thing,

shrewd and secretive.

I want my own will, and I want simply to be with my will,

as it goes towards action,

and in the silent, sometimes hardly moving times

when something is coming near,

I want to be with those who know secret things,

or else alone.

(from the Book of Hours, trans Robert Bly)

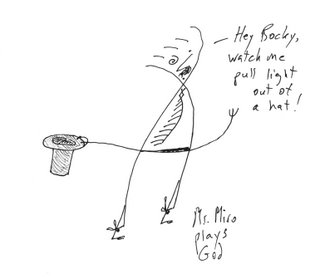

The cartoon refers to a story in the zen tradition, where the students ask, what is the nature of the moon?

The cartoon refers to a story in the zen tradition, where the students ask, what is the nature of the moon?

I was walking across the main bridge in our little town, looking down and noting that the river looks like a real river today--which is a little scary in itself--and then noticed that the wind was blowing so hard that I had stopped moving forward.

I was walking across the main bridge in our little town, looking down and noting that the river looks like a real river today--which is a little scary in itself--and then noticed that the wind was blowing so hard that I had stopped moving forward. I don't really like the Doors.

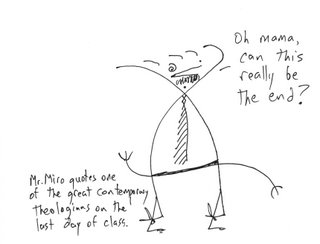

I don't really like the Doors.

This hardly seems like the right cartoon to leave my loyal readers with for the next week, but I haven't had time for the "cookie" series this week, and I doubt I'll be able to post for the next week.

This hardly seems like the right cartoon to leave my loyal readers with for the next week, but I haven't had time for the "cookie" series this week, and I doubt I'll be able to post for the next week. Whenever I think of the ontological argument (and I do that as little as I can, but Anselm keeps popping up these days), I think of an example I used primarily back when I taught at Radford.

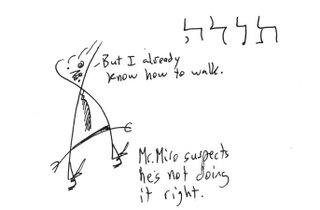

Whenever I think of the ontological argument (and I do that as little as I can, but Anselm keeps popping up these days), I think of an example I used primarily back when I taught at Radford. And it doesn't seem to be getting done today.

And it doesn't seem to be getting done today. I need to be reading about St. Scholastica and Hrotsvit of Gandersheim, as well as Kathryn Tanner's Jesus, Humanity and the Trinity, which I don't particularly like.

I need to be reading about St. Scholastica and Hrotsvit of Gandersheim, as well as Kathryn Tanner's Jesus, Humanity and the Trinity, which I don't particularly like.

Today is yet another busy day, although at this point it looks as though I'll get everything done.

Today is yet another busy day, although at this point it looks as though I'll get everything done.